Research has shown that education plays a large part in how much we earn, but doesn’t fully explain the social origin pay gap. So, in my PhD thesis, I asked if cultural and social capital could be factors.

What is social and cultural capital?

‘Social capital’ refers to our networks and connections, made through our families, work and social activity, while ‘cultural capital’ encompasses our education, things we have in our home (art, books etc.), and our speech, mannerisms, and linguistics.

It is well established that people from more affluent backgrounds invest more in education for their children, leading to greater employment prospects, higher earnings, and influential social networks. These people are also, on average, more ardent consumers of culture – spending more time going to art galleries and museums, going to the theatre or taking part in sports more associated with affluence such as polo or horse riding. Engaging with culture in this way is not just down to education; often our social networks and cultural preferences are intertwined. Although our social circles can influence our cultural interests, we can also choose to go to the ballet or opera, for example, as a way to join – or be seen to be part of – a particular social group.

So, social and cultural capital can reinforce each other, and existing research has looked at how they can help people find their way into professional and managerial roles and establish ‘fit’. This is the first work to empirically examine their potential role in explaining the social origin pay gap – that is: can these factors at least partly explain differences in pay for equally qualified individuals from different class backgrounds?

Measuring social and cultural capital – and social origins

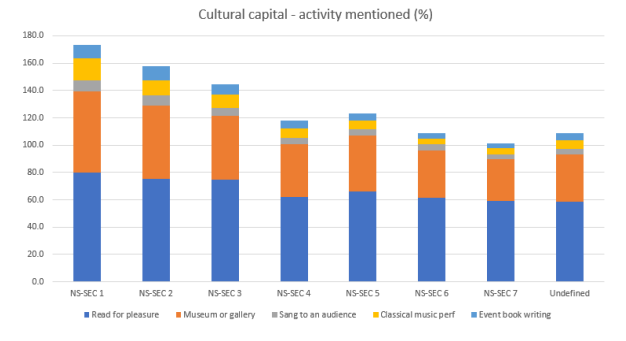

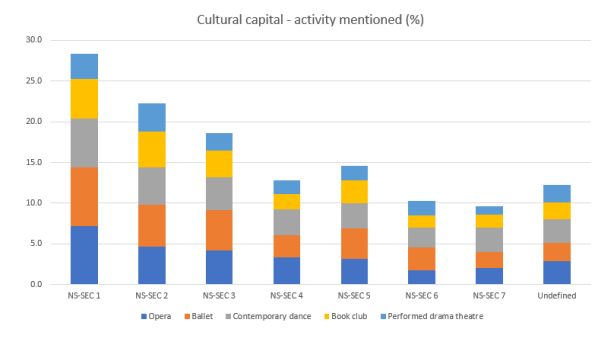

I used data from Waves 1 to 9 of Understanding Society, covering the years 2009 to 2019. In Waves 2 and 5, the Study asked participants a series of questions about their cultural activities in the previous year. The questions include whether individuals have attended ballet, the opera, or an art exhibition, or if they’ve been to a book club, or written stories or music.

To measure social capital, I used answers to questions about people’s social networks, such as: how they met their closest friends, their friends’ employment status and ethnicity, and the proportion of friends who are of similar age, education and income level.

To understand people’s social origins, I used the National Statistics Socio-economic classification (NS-SEC), which proxies people’s social class background according to their parents’ job(s) when they were 14, from higher management and professional to routine. However, I also consider those with ‘undefined’ social origins. This includes people whose parent(s) were economically inactive, and those who did not live with their parents at that age – which may be because the child was in care, or those whose parents were deceased or in prison. They’re a significant part of the sample, and their labour market outcomes are on average much worse than those with ‘defined’ social origins.

- NS-SEC 1 Higher management and professional

- NS-SEC 2 Lower management and professional

- NS-SEC 3 Intermediate

- NS-SEC 4 Small employers and self-employed

- NS-SEC 5 Lower supervisory and technical

- NS-SEC 6 Semi-routine

- NS-SEC 7 Routine

Cultural engagement and social origin

There are stark differences in cultural engagement in relation to social origin. People from professional and managerial backgrounds are much more likely to report engaging in ‘highbrow’ cultural activities. Their engagement is particularly high in activities such as ballet and opera – and those from working class families report the lowest levels of cultural engagement.

Essentially, people from affluent backgrounds are more likely to engage in activities that signal and reinforce their social position, which can benefit them in the labour market. It’s not that going to the opera increases a person’s salary per se, but engaging in ‘highbrow’ cultural activities is an indicator of high social status, which can influence our networks, help build rapport with senior management and clients, and increase our exposure to other high-status individuals, all of which can improve our career prospects. It’s difficult to establish specific causal effects though, because highly educated people are generally more likely to participate in ‘highbrow’ cultural activities, so we can’t eliminate that as a factor. We also can’t tell how often or why people went to the opera, for example – was it personal choice, or a work event?

Social capital and social origin

We see something similar in social networks.

People with more advantaged backgrounds tend to have parents who help them with their education, work experience, university applications, and CVs. In this study I found that those from upper-class origins are most likely to have met their best friends at university or through an organisation or activity. They form a network of people with similar backgrounds and levels of education, who can help each other navigate the labour market. Here we observe a clear disparity in ‘information capital’ across individuals’ social class backgrounds.

Those from upper-class origins are also most likely to have friends in employment, while those with undefined social origins are the least likely. Those from working-class origins are most likely to have met their friends in the neighbourhood or at school, and to have friends who have similar levels of education – which, given the results in another chapter of my thesis, is generally low levels of education.

Overall, then, people from less advantaged backgrounds have less affluent networks, and lower incomes – and fewer friends and family members who are likely to be able to support them financially at a time of need. In other words, people who are less likely to need financial support are more likely to find it available, and those who are more likely to need to borrow money at some point are less likely to find it possible.

Pay gap results

Looking at the pay gap longitudinally, and taking into account cultural capital, educational attainment and a range of labour market attributes, I found significant pay gaps for all social origin groups compared to those whose parents worked in higher management or professional jobs. In particular:

- people with undefined social origins earned 8.9% less than those with the same qualifications whose parents worked in higher management or professional jobs

- those whose parents were self-employed earned 8.7% less than people with the same qualifications whose parents had higher management or professional jobs

- individuals whose parents worked in routine jobs earned 7.4% less than people with the same qualifications whose parents were higher management or professionals.

My analysis had controlled for cultural capital, so I could see that it did not fully explain the social origin pay gap.

When I took social capital into account, along with educational attainment and other key labour market factors, such as occupational status, I found significant pay gaps for those with undefined social origins, and those from NS-SEC-4 to NS-SEC-7 origins. Specifically:

- people whose parents were self-employed earned 8.3% less than people with the same qualifications whose parents had higher management or professional jobs

- individuals with undefined social origins earned 7.9% less than people with the same qualifications whose parents had higher management or professional jobs.

Overall, I found that social and cultural capital play a part in explaining the social origin pay gap, but don’t explain it completely. The educational advantage from a better-off background is still significant. The pay gaps are smaller when controlling for social capital, which may be a sign that this is more significant than cultural capital.

In future, it would be interesting to be able to look at which university people have attended, because people who went to an ‘elite’ university are over-represented in the most powerful and influential positions in UK society. I would also like to look at different measures of cultural capital such as accent, vocabulary and mannerisms, which Understanding Society doesn’t currently measure, and how respondents report these play a role in their career

I think it’s vital that we keep exploring the social origin pay gap. It significantly affects large numbers of people, but also it has wider implications for social justice, the value of education, and the country’s economic performance.

Authors