Government policies are often designed to tackle social problems, and – as a result of that – many will also impact people’s health and wellbeing. Understanding Society, and the many other longitudinal studies in the UK and worldwide, can help us to assess the health impact of policies, pointing out where and how they have benefited us, but also highlighting potential harms and opportunity costs. In this blog, based on a presentation I gave at September’s Society for Longitudinal and Lifecourse Studies (SLLS) conference, I want to illustrate how our health is influenced by social and economic policies throughout our lives, in ways that are not easy to anticipate.

Maternity leave

Let me start with a clear example of a policy that matters to women’s health: paid maternity leave. Being able to take weeks or months of leave around childbirth while continuing to be employed provides women with time to recover from childbirth, interact with their new-born child, and kick-start its early development, while also helping women to remain in the workforce. A paper I co-authored, using data from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), looked at women in later life (50+) and what sort of maternity leave policy had been in place for them in several European countries from 1960 onwards when they had their first child in their 20s or 30s. We found that a longer maternity leave during the birth of a first child led to a significant reduction in women’s risk of depressive symptoms many decades later, when they were 50 years and older. Our findings are in line with many studies showing the benefits of early expansions of maternity leave in many European countries.

And yet, research from 2013, which looked at a series of policy reforms from 1987 to 1992 that expanded paid maternity leave from 18 weeks to 35 weeks in Norway found little effect on children’s school outcomes, parents’ earnings, or on their participation in the labour market in the short or long term. This, despite the fact that the initial 1977 reform that introduced 18 weeks of maternity leave benefits in Norway did find positive effects across a range of outcomes.

Few of us would argue that maternity pay isn’t a good thing, but why do we find contradictory effects across different reforms? What this shows is that to be able to argue that paid maternity leave benefits bring health improvements, we must be specific as to exactly what policy we are talking about – for how long, under what conditions, and for which target populations. This is important because specific policies have different effects, depending on what aspect of them we’re considering. In Norway, previous studies indicated positive effects from the introduction of 18 weeks of maternity leave; however, extending it to 35 weeks did not yield positive effects. This is because we are essentially discussing two distinct policies.

In other words, the specific policy and how it is implemented are important. For example, research has shown us that many social determinants are linked to health:

- mothers’ education levels strongly predict their children’s later BMI – mothers with lower secondary education had heavier children than mothers with degrees

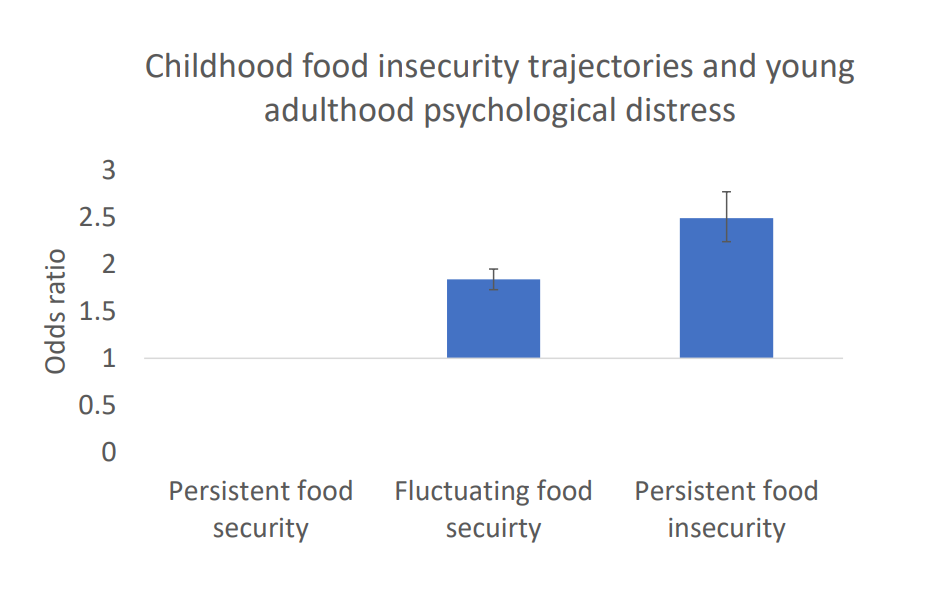

- growing up with persistent food insecurity placed children at greater risk for mental health problems

- having an unemployed father made teenagers much more likely to be on anti-depressants.

However, while we can see patterns here, we can’t be certain about the health impact of a specific policy that would intervene on these social determinants.

Social factors

We’re talking about policies which governments put in place to improve the social wellbeing of people and communities. They shape not health itself but the social factors which are potentially linked to health, such as economic stability, education, poverty, unemployment, housing, and the urban environment.

This idea of health having ‘social determinants’ is backed up by the World Health Organisation, which says “policy in every sector of government can potentially affect health and inequities in health”. It’s also supported by Sir Michael Marmot, one of the leading researchers on health inequality, who writes about social policies reducing disparities by addressing the “root social causes” of poor health, such as poverty.

If this is the case, we should apply the same standards to social policy that we do for health policy – by establishing whether they lead to improvements in health. As with health, there are likely to be both effective and ineffective social policies, and longitudinal data can help us to evaluate them.

Unpredictable outcomes

Policy outcomes are not straightforward, though. Governments do not simply make decisions and watch the intended effects smoothly rolling out. The impact depends on how people respond, which is often difficult to predict. Also, the specific mechanisms the government chooses may have health effects that are unknown in advance.

Longitudinal studies allow us to track short- and long-term changes in social and health outcomes by repeatedly measuring them over long periods of time. We can look at people’s lives before and after a policy change to observe its effects, helping to establish causal relationships and identify diverse and unexpected effects.

Surveys which look at families and households over time can also show us intergenerational effects of social policy. Policies that target parents might enhance child development, for example, by improving educational opportunities and outcomes, or changing social norms around health behaviour. Policies that target younger generations, such as increased schooling, and better education, might affect older parents, perhaps by enhancing the capacity of adult children to care and provide support for older parents.

To illustrate the complexity of policy effects, I want to look at three case studies, all using longitudinal data, each one looking at the health impact of different social policies.

- Compulsory schooling

We know that education is closely linked to health, with more educated people enjoying longer lives, and being in better health while alive, but there has been little research on the mental health effects. We know that people with higher education tend to have better mental health, so we might assume that being in education longer is associated with better mental health. Data from Understanding Society, the Annual Population Survey, the UK Biobank, and the National Child Development Study allowed my co-authors Vahe Nafilyan, Augustin De Coulon and myself to examine the effects of the UK’s change in 1972 which saw the school leaving age rise from 15 to 16.

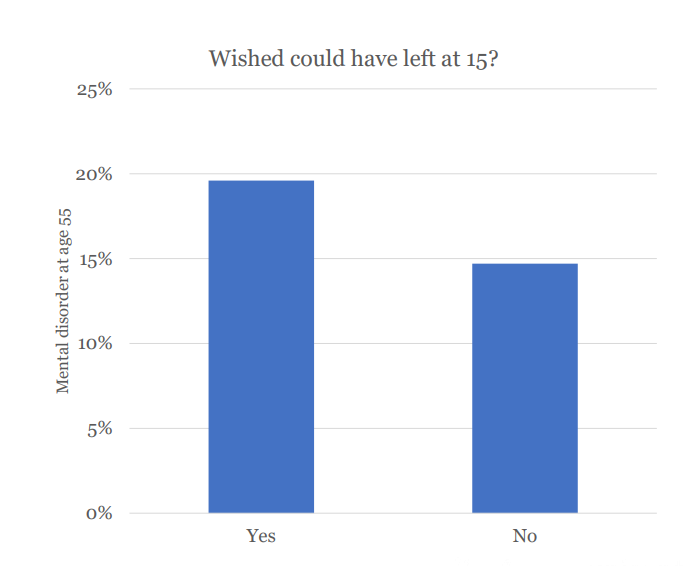

Looking at people before and after the change, we found no positive effect on mental health – and, for some people, more self-reported diagnoses of depression and anxiety. Our results showed that making people stay in education for longer affects their mental health, but not through educational attainment. Although people stayed in school longer, they didn’t necessarily go on to university. We also found that a year of extra schooling increases the probability of a mental health condition later in life by 3.9 percentage points. In addition, people affected by the change were asked if they wished they could have left school at 15, and those who said yes were more likely to have a mental disorder later.

So, the picture is more complicated than it appears at first, and there are several possible explanations. It may be that people who don’t benefit from formal education are negatively affected because the returns from an extra year of school for them are overshadowed by the fact that they could not enter the labour market earlier. Forcing people to remain in a competitive academic environment may also, for some students, have psychological and emotional costs, particularly for students who are less oriented towards learning.

Raising the school leaving age may not always improve people’s health, then. The point here is not that education does not matter to mental health – it may well matter. Instead, the point is that the way policies act to increase educational attainment – in this case, by making it compulsory for all individuals of a certain age to stay longer at school – may have had negative effects on mental health that were unanticipated by decision makers. Other education policies may have completely different effects on mental health, which highlights the need to understand the specific mechanisms by which specific social policies might impact health.

- Lone parents

In the UK, there were three million lone parent families by 2021, around 15% of families with children, most of which were headed by lone mothers. There has been a considerable increase in recent decades in the proportion of these women who are working – from 44.2% of them in 1999 to 65.1% in 2022, one of the largest increases in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, which comprises 38 of the world’s most developed, high-income economies).

Since 2008, this increase has largely been attributed to the expansion of welfare-to-work programmes, which made child and family benefits conditional. Before November 2008, lone parents in the UK got unconditional Income Support until their youngest child was 16. After this date, they had to be actively looking for work in order to get the benefit. The youngest child age threshold was gradually reduced to 10 (2009), 7 (2010), 5 (2012), and 3 (2017). Parents either had to seek work or move to other benefits.

In theory, this could have either positive or negative effects on health. It might increase women’s work supply and income, which may improve the conditions in which the family lives. Being in the workforce could also improve lone parents’ social network, with positive effects for the children. On the other hand, these parents might only be able to get low-paid jobs, which are less stable, making their income precarious, and conditioning benefits on work might lead to psychological distress.

Using the Millennium Cohort Study, my co-author Liming Li and I found that the reform increased lone mothers’ employment and income, but did not reduce the risk of family poverty. We looked at their children’s scores on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, which measures emotional and behavioural problems in children and teenagers (ages 2-17). There was a small but statistically significant increase in teenagers’ SDQ scores, signalling a negative effect on their socioemotional development. What might explain this? Something we found was that there was also an increase in mothers’ psychological distress and poor self-rated health, and in the probability that they reported not having enough time to spend with their children. This could be having a knock-on effect on their adolescent children’s mental health.

- State pension age

In our final case study, we examine a common policy in OECD countries: increasing the age at which people can start claiming the state pension. In the UK, there has been quite a large increase for women. Many studies show that for pensions to be sustainable, the age at which people can claim them needs to rise, but what is the effect on the mental health of the women who are affected?

The effects on health could, again, be either positive or negative. On the one hand, working longer can increase income and provide individuals with a sense of purpose. On the other hand, some women may not be able to continue working and may experience a reduction of income, or they may be exposed to poor quality jobs, leading to psychological distress. My co-authors Ludovico Carrino, Karen Glaser and I used Understanding Society to look at people’s answers to the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), which measures psychological distress.

We found that the policy achieved what it intended to: women who find themselves below the state pension age as a result of the reform are more likely to work than those above the stage pension age. However, being under state pension age as a result of the reform increased the probability of depressive symptoms by 6.2 percentage points. And it didn’t affect women equally. The effect was driven by women in jobs which were demanding, and over which they had little control – in other words: women in lower socioeconomic positions, who saw a small negative effect on their physical health as well.

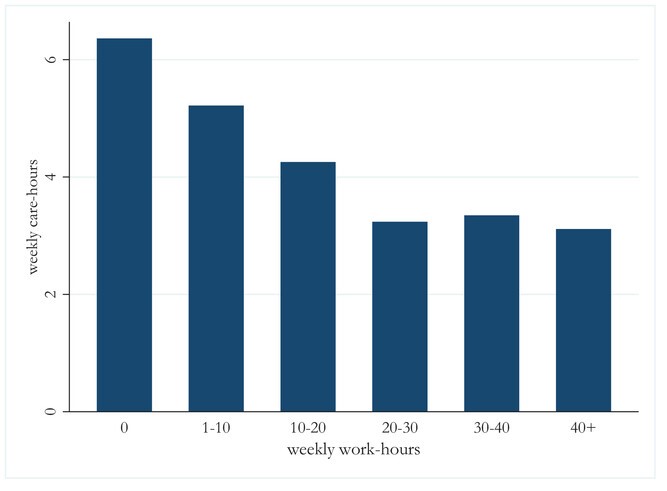

In a further piece of research, again using Understanding Society, there was evidence of a trade-off between work and providing care for older relatives – which is most often done by women. An increase of 10% in working hours leads to a 3.7% drop in the number of care hours provided – and again, the effect is larger for women in psychosocially or physically strenuous jobs. The policy had also intergenerational effects: Using data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing, we showed that when the eldest daughter is not eligible for a pension, her older parents receive less help – and this reduced care is not compensated for by formal or informal care from other sources.

What we’ve learnt

Overall, we can say that social policies often have unexpected health effects – which the people behind those policies often didn’t expect at all, or at least, did not factor into their evaluation of the policy’s merit. There can also be ‘ripple’ effects, where the impact is felt on multiple generations (affecting either children or older parents).

Unpredictable effects – and the fact that people are unpredictable, too – make it difficult to anticipate what the health effects of any policy might be, good or bad. Also, there is often a trade-off between valuable social policy goals and health objectives. This is true in the case of each of the case studies above, especially in relation to mental health. It may be good to increase employment in older age for the sustainability of pension systems, but it comes at the cost of mental health deterioration.

What we can say for certain is that longitudinal studies are vital for understanding the health impacts of social policies, especially when linked with data on policy changes. By following people, and sometimes whole households, over time, they allow us to observe changes before, during, and after a policy change – these so-called ‘natural experiments’ can not only help us understand the health impact of policies, but they may also reveal important features of human behaviour that may help us advance social theory.

According to the National Audit Office in 2021, only 8% of major government projects are robustly evaluated, with 64% not evaluated at all. Longitudinal data is hugely important, then, not just in seeing how effective government spending is, but in seeing the full picture of the effects on all our lives.

Authors

Mauricio Avendano

Mauricio Avendano is Associate Professor at the University of Lausanne, and co-director of the Health Economics & Policy Unit at the Department of Epidemiology and Health Systems at Unisanté. He is also adjunct Associate Professor at Harvard University