Over time, marrying for life has become less common, with more people having more than one long-term relationship during their life. Research has shown a gender gap in ‘re-partnering’, with men more likely to enter a new relationship after the end of a previous one than women.

One of the main reasons for this is the parenthood ‘penalty’ – finding a new partner is more challenging for people who have childcare responsibilities. This is particularly difficult for women, who are more likely to live with their children after a break-up. However, parental status does not explain all the gender gap, which is very consistent across studies.

We argue that we can better understand this gender gap by studying re-partnering dynamics among lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) people. So far, research on re-partnering has assumed that people are heterosexual and form relationships with someone of the opposite gender/sex. We aimed to overcome this limitation by leveraging Understanding Society’s survey question about sexual identity to test whether the same gender gap exists among LGB people.

The main argument

What can we learn from re-partnering behaviour among LGB people? First, it is important to remember that there are demographic differences between these two groups. LGB people are less likely than heterosexuals to be married or living together with a partner, and in some countries same-sex couples are more likely to separate than different-sex couples. Also, the LGB population skews younger, and are less likely to have children.

But the most important difference between these groups, of course, is that many LGB people partner with someone of the same gender/sex. This changes the role that gender plays in relationships dynamics and can change what women and men expect and get out of relationships.

Gender dynamics are often unequal within different-sex relationships. Heterosexual women invest more time and emotion in their relationships with men. This investment is costly and could make forming a new relationship less appealing for straight women. Straight men, getting more from a relationship, have more incentives to start again. Same-sex relationships, in contrast, tend to be more egalitarian, with partners sharing expectations about the relationship and the division of labour. However, lesbians are more attentive, look after their partners’ health, and work on intimacy more than gay men do. This could increase the incentives for them to enter a new relationship compared to gay men.

In other words, lesbian women can have more incentives to re-partner compared to heterosexual women, whereas this is the other way around for gay men. For bisexual people, this might depend on the gender/sex of former and prospective partners, and re-partnering gaps might therefore fall in between those observed for heterosexual and gay/lesbian people.

Using the data

We used Understanding Society data from 2009 to 2019, working with the hypothesis that lesbian women will be more likely to re-partner than gay men, and that differences between bisexual men and women could be smaller (because some bisexual people have partners of a different gender/sex and others have partners of the same gender/sex).

Understanding Society offered a unique opportunity, being one of the few nationally representative longitudinal surveys that collected people’s relationship histories (Waves 3 and 9) – similar to past re-partnering studies – but also sexual identity (Waves 1 and 6), which allows us to distinguish between heterosexual and LGB women and men. We controlled for age, birth cohort, race, parental status, and education.

It’s important to point out that our sample size was small for LGB people – a common problem for studies of the LGBTQ+ population. The prevalence of LGB identities is generally still below 5% across surveys (although that percentage is increasing rapidly across younger birth cohorts). We looked at 13,274 heterosexual people and 387 LGB women and men – 122 lesbians, 83 bisexual women, 128 gay men, and 54 bisexual men. Nonetheless, our results are stable for different analysis strategies.

Our findings

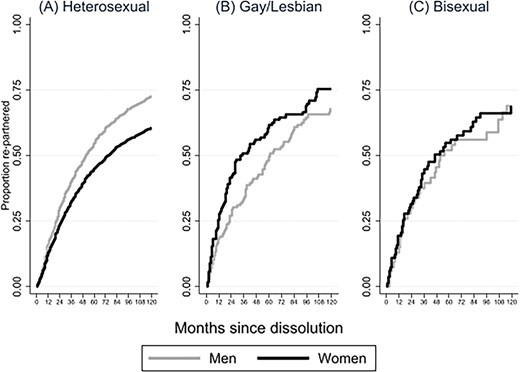

Our results confirmed that heterosexual men are more likely to re-partner than heterosexual women. The gap starts to emerge two years after the first relationship breaks up, and remains throughout the ten-year period we looked at. Within those 10 years, 73% of the heterosexual men in the sample re-partnered compared to 61% of heterosexual women.

However, we also found that lesbians were more likely to re-partner and do so faster than gay men. After a year, 28% of lesbian women had re-partnered, compared to 19% of gay men. After 10 years, the figures were 75% of lesbians and 68% of gay men. Limiting the sample to lesbian and gays who are not residing with children did not alter the results.

We found a smaller gender gap among bisexuals, though. Nineteen per cent of bisexual women re-partnered within the first year after the first break-up, compared to 15% of bisexual men – although the trend gets less clear as time goes on. After 10 years, 69% of bisexual women and men re-partnered.

Our conclusions

We found that the re-partnering gender gap – wherein men are more likely to re-partner – is limited to people who identify as heterosexual. Among gay/lesbian individuals, we found that there is a gender gap, but in the opposite direction. Lesbians are more likely to re-partner than gay men – and than heterosexual women. We did not find clear gender differences among bisexual people.

There are numerous possible explanations for this pattern. In our paper, we propose that this indicates how gender dynamics and sexual identity shapes relationship formation outcomes. If lesbians have more incentives to re-partner than straight women do, because having a female partner implies receiving more from a relationship, this context is critical for understanding relationship decisions and changing patterns among women and men in the general population.

Authors

Ariane Ophir

Ariane Ophir is a Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral fellow at the Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics (CED-CERCA)

Diederik Boertien

Diederik Boertien is Head of the Families, Social Change and Inequality unit at the Centre d’Estudis Demogràfics (CED-CERCA)