“Of what use are statistics if we do not know what to make of them? What we wanted at that time was not so much … an accumulation of facts, as to teach the men who are to govern the country the use of statistical facts.”

These are not my words – nor, indeed, the words of any social science researcher. They come from a letter Florence Nightingale wrote to a friend in 1891. Although she is still often thought of as a pioneer of (wartime) nursing, Nightingale’s real breakthrough was in statistics and data visualisation.

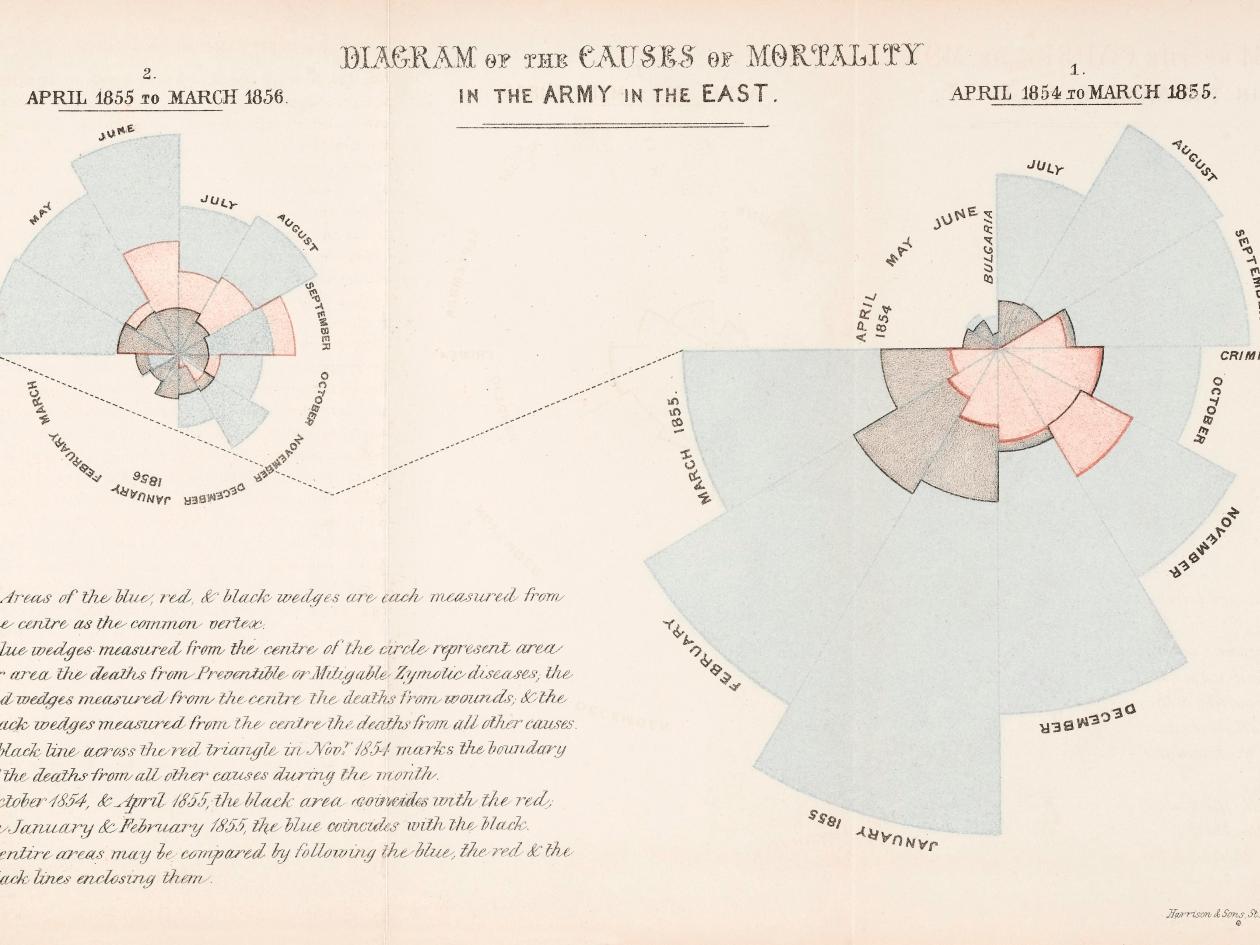

In 1854 in Crimea, hygiene levels were so poor that ten times as many soldiers were dying from preventable illnesses such as typhus and dysentery than from battle wounds. Nightingale brought in a new hygiene regime, and noted the reduction in preventable deaths.

After the war, she outlined her recommendations, but the government ignored them – so she created data visualisations, which clearly showed the causes of death in Crimean hospital camps, and distributed them widely. Her recommendations were adopted, and she became the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society in 1859 and later an honorary member of the American Statistical Association.

One country, two systems – not quite

Over 160 years later, many researchers dream of having such influence. Our new report, Transforming Social Policies, aims to give them insights into policymaking, and to help researchers and policymakers raise their game in working together to tackle society’s challenges.

The rich set of large longitudinal studies we have in the UK are ideal for understanding how people interact with the world around them, and to identify the causes and consequences of change on individuals, families and groups.

In the first of my three blogs on the report, I look at knowledge mobilisation and how longitudinal research can more effectively inform policymaking. As we have seen in the last few months, there has been a significant scaling up of collaborations between researchers and policymakers in response to COVID-19. This has been helped by a temporary cessation of Britain’s highly bi-partisan politics and the singularly challenging focus across government on tackling the crisis.

Understanding Society is playing its part in helping assess the effects of the health crisis, with briefings on the economic effects, health and caring, home schooling, family relationships, and ethnic differences in the pandemic’s impact (PDFs).

The interaction between the world of social science and policy is driven by the Haldane Principle, but as Sir Paul Nurse identified in his report, there is a need for greater synergy and coordination. However, supply driven models of knowledge transfer can be simplistic in their design, particularly when faced with the dynamic and short-term, and often chaotic, world of policymaking.

Researchers can understand more about the evidence needs of individual government departments by looking at their published areas of research interest (ARIs) – although it’s early days in assessing the extent to which these can be a catalyst for productive working between academics and government departments.

Each ‘sector’ and system has its own structures, incentives and ways of working that can constrain how evidence, ideas and policy interact – some of these barriers are explored in the report. One real key to policy influence is long-term relationship building: getting to know policymakers, being seen as a reliable source, and perhaps gaining a reputation as a subject expert.

However, if social policies are to be more transformative of people’s lives, we need to look for new and effective ways of adding value to research and building productive collaborations.

Framing

The first lesson for researchers is that, while scientists focus on what we don’t know, what’s not being measured, or knowledge which is contested, policymakers are likely to be interested in the latest thinking and evidence, and in summaries of what we do know – which can be foundations for policy thinking.

Critical to reducing information asymmetries between researchers and policymakers is tackling the availability bias! The growing volume of accessible data and analysis means that how research is framed, narrated and visualised, and its timing, is important in capturing policymakers’ attention – and engaging policymakers can help stimulate future demand for evidence.

This is where academic expertise can help, by articulating and interpreting the problem, and placing research into a wider perspective and policy landscape. In short, academics need to be able to tell stories – to set out their facts in the context of an unfolding narrative to give them meaning.

Joined-up thinking and team science

We are increasingly living in an era of large, collaborative and challenge-orientated research projects that reach across traditional academic disciplines and professional boundaries. These require partnerships, akin to the kind of team that would be assembled for a design, engineering or construction project, with multidisciplinary expertise drawn from social sciences, humanities or other sciences, and supported by communications, impact or other specialists.

This is how we need to think about research – but it can also guide how some aspects of policymaking need to change. Fixing specific social problems depends on many factors, including ‘joined-up government’, and while policymakers do see the need to work cross different kinds of boundaries, such cultures take time to change.

Looking over the horizon

The fast-paced nature of policymaking means that time to reflect is short. Policymakers live under the pressure of launching symbolic policies, coping with crises, (three-year) spending cycles, and elections, driven by ideas that are broadly politically acceptable at the time. As anyone living in 2020 will clearly understand, the best-laid plans are often derailed by unexpected events. The rhythms of social science and policy are not always easy to synchronise.

But, in the words of marine and polar scientist Ian Boyd – former Chief Scientific Adviser to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs – “Most of my role is about looking from a scientist’s perspective at what the world is going to look like in 10, 20 or even 40 years’ time, and how we need to structure policy or the department itself to meet those challenges.”

Developing new and effective ways of collaboration is challenging, but the rewards are significant, not just for researchers themselves and their university’s REF performance, but for transforming social policies. There is public appetite for change and now is the time to act!

The Transforming Social Policies report is published on Friday 16 October

Authors

Raj Patel

Raj Patel is Associate Director, Policy and Partnerships, at Understanding Society