Several studies have shown that Londoners have worse wellbeing and poorer mental health than people in other parts of the UK. Research that explores what influences Londoners’ wellbeing and what can help is therefore much needed. Our report, co-authored by the Mile End Institute at Queen Mary University of London and Centre for London, takes up precisely this challenge.

Our analysis measures wellbeing using the Warwick-Edinburgh mental wellbeing scale, which is included in the Understanding Society survey every three waves, scoring respondent wellbeing from low (7) to high (35) by combining responses to questions such as how optimistic they’ve been feeling about the future.

Using the data

First, we analysed this data longitudinally to explore whether moving in to, or out of, London affected wellbeing. If there was something specific about living in London that worsened our wellbeing, we would expect to see individuals’ wellbeing decline after they move to London and improve when they leave. We don’t see this pattern. Instead, we find wellbeing decreases after both kinds of move, on average – suggesting it is the experience of relocating that impacts wellbeing, rather than the experience of living, or not living, in London.

We then turned to analysing this data cross-sectionally, using the most recent wellbeing measures available (Wave 10, 2018-19). Again, we found no support for the idea Londoners have worse wellbeing outcomes. When all 12 UK government office regions were ranked according to residents’ average wellbeing scores, London ranked in the middle at 6th highest, scoring 24.54 (compared to Northern Ireland, the highest at 25.13, and Wales, lowest at 23.96).

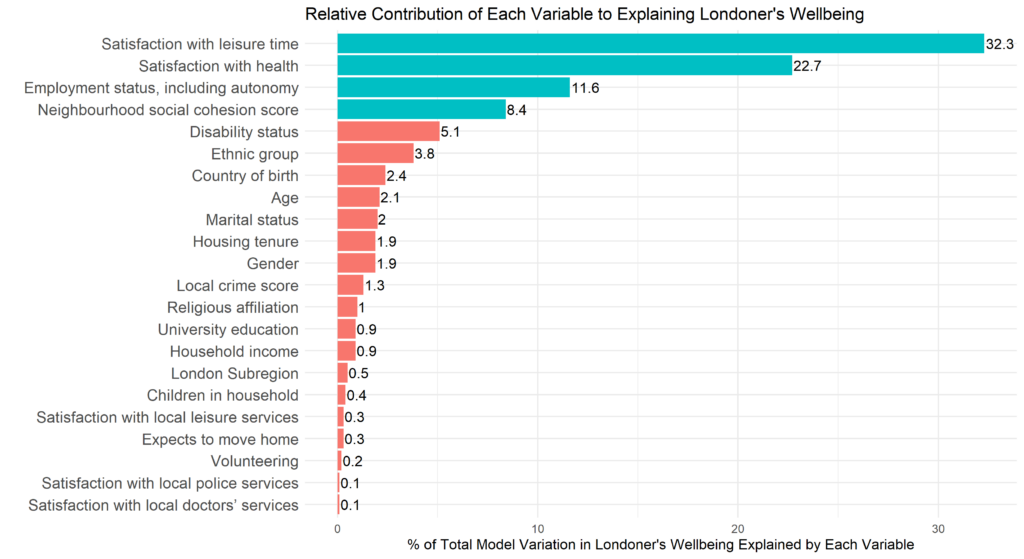

Multiple regression analysis was then used to identify the key determinants of wellbeing in London. This method allowed us to quantify the association of various different factors with wellbeing outcomes, after accounting for the independent effects of all others. Our regression model indicated four variables with particularly strong influences on Londoners’ wellbeing:

- how satisfied people are with their leisure time

- how satisfied people are with their health

- whether people work, and if so, how much autonomy they have in their role

- the level of neighbourhood social cohesion where people live.

Together, these variables accounted for 75% of the variation in Londoners’ wellbeing outcomes explained by our model. Satisfaction with leisure time clearly had the most important influence on wellbeing in London, followed by satisfaction with health, employment status – including workplace autonomy – and neighbourhood social cohesion. We do not contend these are the only variables that matter when it comes to wellbeing in London, but simply that these account for many of the crucial differences observed in Londoners’ wellbeing outcomes.

Our regression results tell us how each of these four factors influence Londoners’ wellbeing, and how these effects vary depending on other characteristics.

Key influences on Londoners’ wellbeing

Policy implications

What kind of policy changes in these key areas might be effective in increasing the average level of Londoners’ wellbeing, or reducing wellbeing-based inequalities in the capital? Our report suggests actions for local and national government. These recommendations were formulated by reviewing existing literature and through discussion with experts in wellbeing.

When it comes to improving Londoners’ satisfaction with their leisure time and their workplace autonomy, policy ought to focus on giving people more control over the amount of time they have available, and more freedom to use this in ways they find fulfilling. National government could, for example, legislate to make sure shift-workers have adequate notice for shifts, to help them plan their childcare and leisure activities. Also, the Greater London Authority could consider how to include in-work autonomy in their Good Work Standard accreditation programme.

How satisfied people are with their health matters most for wellbeing among Londoners with disabilities and/or long-standing health conditions. Policy should therefore aim to support the delivery of services and design of places that enable people with different needs to participate fully in society. Unhealthy stress can damage people’s health. To reduce it, policy makers should employ wide-ranging approaches to make sure all Londoners have access to a decent standard of living. This includes policies to support Londoners with the rising cost of living and any difficulties they may experience in finding a safe and stable home.

We consulted experts on how to improve social cohesion in London’s neighbourhoods. One approach is to improve policing. With the Metropolitan Police facing historically low levels of public trust, becoming more representative and accountable should be a priority. Community policing is associated with improved cohesion, but there are now half as many community support officers as there were a decade ago. Social cohesion can also be bolstered by providing spaces and services that bring people together. Wide, well-lit pavements encourage people to linger and talk, while children’s centres and older people’s day centres, which have seen significant funding cuts in recent years, provide places to meet others.

We hope the evidence and ideas presented here help decision-makers grapple with the challenges of trying to improve wellbeing outcomes in a complex and rapidly changing world.

Authors

Elizabeth Simon

Dr Elizabeth Simon is a Postdoctoral Researcher in British Politics at the Mile End Institute and Queen Mary University of London’s School of Politics and International Relations

Josh Cottell

Josh Cottell is Head of Research at Centre for London