The 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) had wide-ranging impacts on the global economy, including immense and long-lasting effects on housing markets and insecurity. Economic scarring took place across many nations, and the UK housing market experienced a particularly lengthy recovery period. My work has explored the trajectory of housing affordability in the UK in the years following the GFC. Using data from Understanding Society, I demonstrate:

- the long-term scarring to affordability that still affects UK housing today

- the different effects for mortgaged homeowners and renters

- and the interaction between post-GFC recovery and austerity policies.

The Global Financial Crisis and austerity

The 2007-2008 GFC was a period of worldwide economic crisis triggered by the collapse of subprime mortgage and housing markets in the USA. The crisis generated severe short-term damage to UK housing markets, including significantly reduced property values, transactions, and construction, higher lending requirements for house buyers, and a peak in the number of repossessions of mortgaged properties.

The post-GFC downturn in UK housing markets is linked with several current trends in housing insecurity. The crisis and subsequent housing market responses were characterised by a growth in the private rental sector and an increase in households dependent on private rental for long-term accommodation. The increased prominence of the private rental sector is problematic in a UK context because of high levels of insecure tenancies and unaffordable housing. Following the crisis, many UK households, particularly homeowners with mortgages, experienced an increased risk of household debt. Other research links the financial crisis with long-term decreased housing opportunities (particularly in the form of affordable home ownership and rental costs) in the UK, privileging home ownership and limiting choice and mobility for much of the population.

The UK’s more long-term response to the effects of the GFC included the 2012 Welfare Reform Act, introduced by the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition. The reforms aimed to reduce perceived welfare dependency and spending by centralising the welfare system and incentivising work. The reform package included the introduction of Universal Credit, an integrated benefit for all working age claimants. The reforms have been linked to an increase in financial and housing precarity for some claimants. Several studies have linked the introduction of the welfare reforms with intensifying the persistence of the GFC’s long-term effects on financial and housing precarity in the UK.

Exploring post-GFC housing affordability

To explore the post-GFC trajectory of housing affordability in the UK, I used a combination of Understanding Society and British Household Panel Survey data from 2003 to 2023. Understanding Society/BHPS is a large, nationally representative panel study of UK households, collecting annual interview data on a variety of social and economic topics. The sample for this analysis includes all working age (18-65) social or private renters or mortgaged homeowners, excluding outright homeowners living in England. The dependent variable is a binary variable of whether the respondent has experienced housing payment problems in the 12 months preceding their interview.

Housing affordability between 2003 and 2023

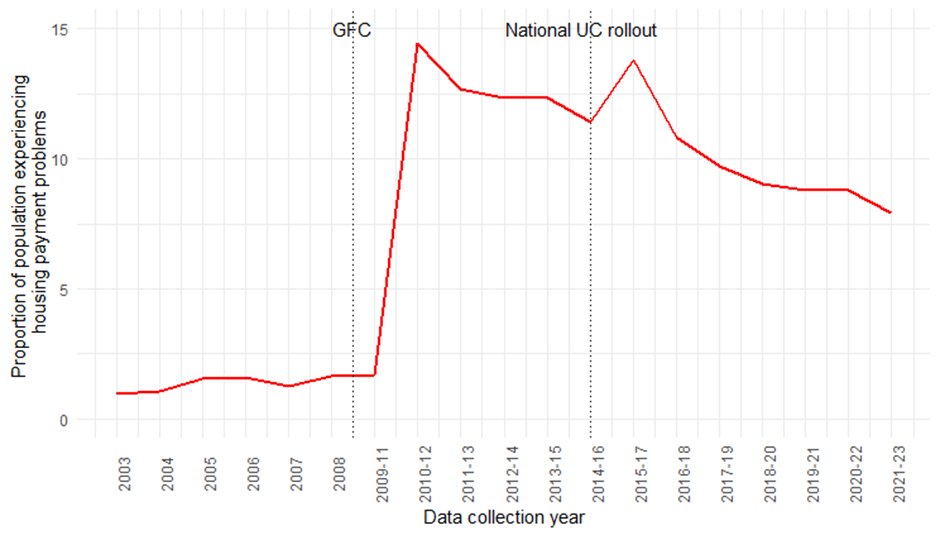

Before the GFC, between 1 and 1.7% of the pre-GFC sample experienced housing payment problems. Visualising the trajectory of housing insecurity for the full sample demonstrates a large rise in housing payment problems at the time of the GFC to 14.4% of the sample, with very persistent effects. The impact of the GFC is followed by a gradual decline in housing insecurity until a small peak at the time of the 2015 national expansion of Universal Credit, a keystone of austerity welfare policy. At this peak, 13.8% of the sample experienced housing payment problems, a 2.2% increase from the previous data collection wave. At the end of this period, the prevalence of housing insecurity remains at approximately twice the level reported before the GFC.

Housing insecurity trajectories by tenure

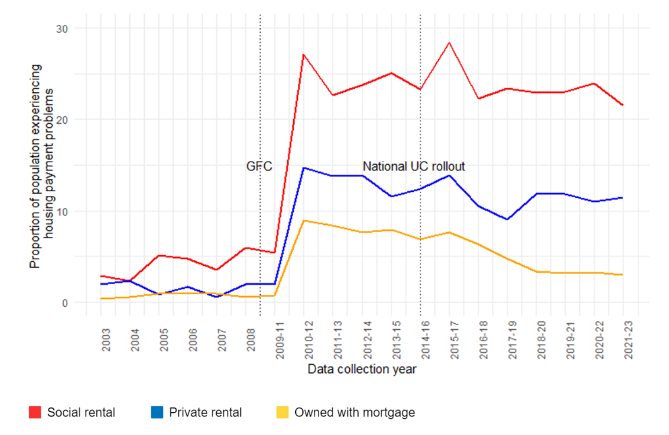

When the sample is broken down by tenure, differing experiences of housing insecurity emerge for private renters, social renters, and mortgaged homeowners. While all tenures experience a significant persistent rise in housing payment problems at the time of the GFC, this spike is more extreme for renters, particularly social renters. At the time of the GFC peak in housing insecurity, 9% of mortgaged homeowners in the sample experienced housing payment problems compared to 14.7% of private renters in the sample and 27.1% of social renters in the sample. Both private and social renters have also recovered less since the GFC and are more vulnerable to spikes connected to crises or economic changes in comparison to mortgaged homeowners – this pattern is particularly severe for social renters.

Conclusion

This analysis evidences the strong and persistent damaging effect of the Global Financial Crisis on experiences of housing payment problems. Rather than supporting recovery, post-GFC austerity policies seem to have, at best, had no real effect and, at worst, further entrenched housing affordability problems. Reduced housing affordability and slow recovery have not been experienced equally, with renters, particularly those in the social rental sector, bearing the brunt of the economic shock. As we grapple with the newer wounds of a housing emergency and high cost of living, it is important to remember that for many the scars of the Global Financial Crisis have not yet healed.

This post was adapted from Rhiannon’s original on the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence blog

Authors

Rhiannon Williams

Rhiannon is an analyst, and wrote this blog when she was a Research Associate of the UK Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence (CaCHE) based in the University of Sheffield Urban Studies and Planning department