Work is a very important factor in health. Generally, employment benefits health through material and psychosocial factors such as the ability to pay for food and a home, and feelings of self-worth. These benefits vary by stress-related factors such as security, pay, hours and autonomy. All this is nothing new. But employment might be only half of the story when it comes to understanding work and health.

Unpaid work has been largely ignored, but some of the stress of work can also be found in unpaid labour, and unpaid labour might influence health indirectly through its impact on employment outcomes and opportunities.

Labour market inequalities

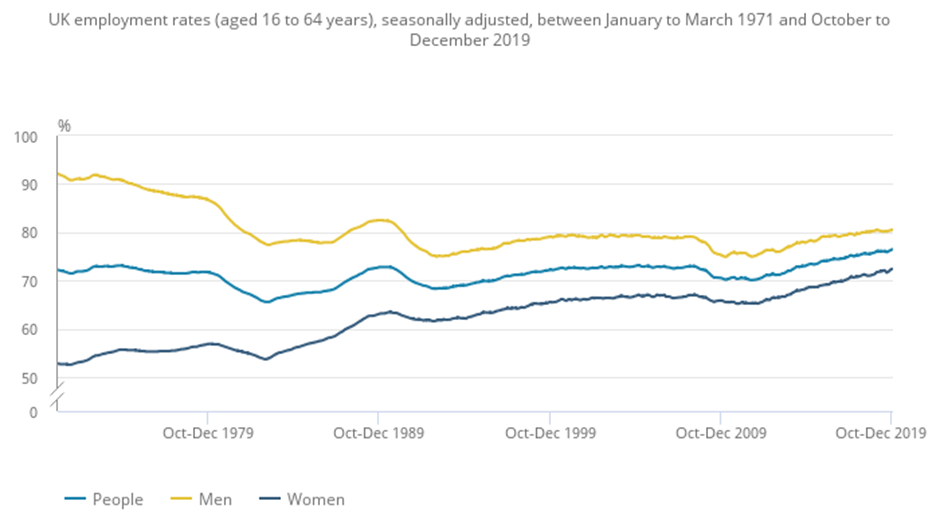

The Labour Force Survey shows us that employment rates for men and women have been converging for years.

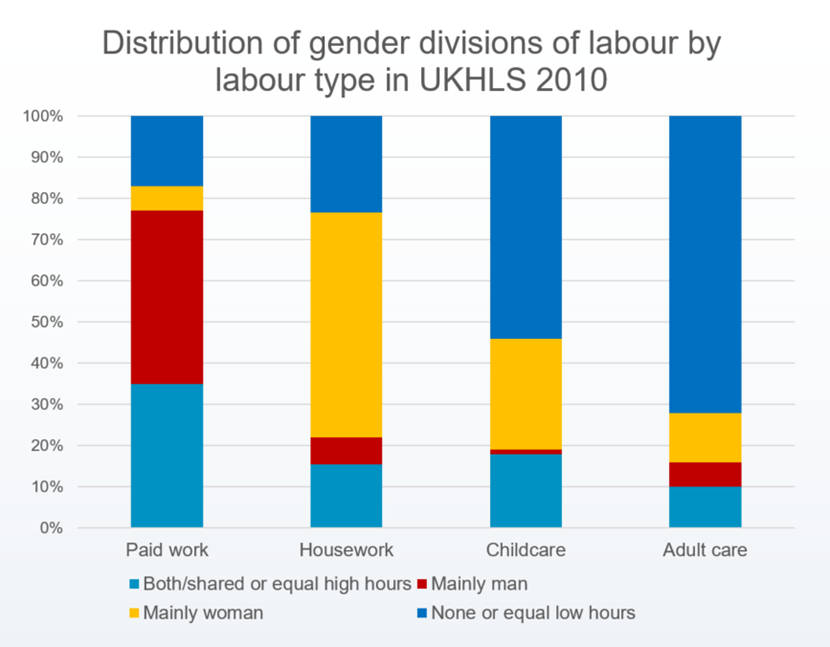

Women continue to do more unpaid work than men in all countries, and are still more likely than men to reduce their work hours in response to care responsibilities, and to work in low paid and precarious sectors. Women also continue to earn less than men and are under-represented in decision-making roles. Gender inequality in the amounts of unpaid labour that men and women do is thought to contribute to these differences.

Some of the figures we have, for example, are:

- average weekly work hours are 35.3 for men, 27.8 for women

- the gender pay gap was 13.1% in April 2024; 7% for full-time employees

- 69% of low paid earners (earning below two-thirds of hourly median income) are women and women are over-represented in precarious and low paid sectors

- 60% of jobs paying below the real living wage are held by women.

Also, while women make up 51% of the UK population, we account for 40% of MPs in parliament, and 44.7% of FTSE 100 directors (but only 30.5% of those in the 50 largest private companies).

Unpaid work

As long ago as 2014, the OECD has recognised that “unpaid care work is the missing link in explaining gender gaps in labour market outcomes”, and more recently the Women’s Budget Group Commission for a Gender-Equal Economy also recognised unpaid care work as being at the heart of gender inequalities.

Before we look at some research, it would probably be helpful to define what we mean by unpaid care work: essentially, all unpaid services provided within a household for its members, including care of people and housework. Care might mean everyday childcare or the usually unpaid help or assistance given to family members or friends with mental and physical health conditions, disabilities, and addictions.

Understanding Society can be a good resource for studying its effects, because the survey regularly asks two questions:

- Is there anyone living with you who is sick, disabled, or whom you look after or give special help to?

- Do you provide some regular service or help for any sick, disabled or elderly person not living with you?

Parenthood

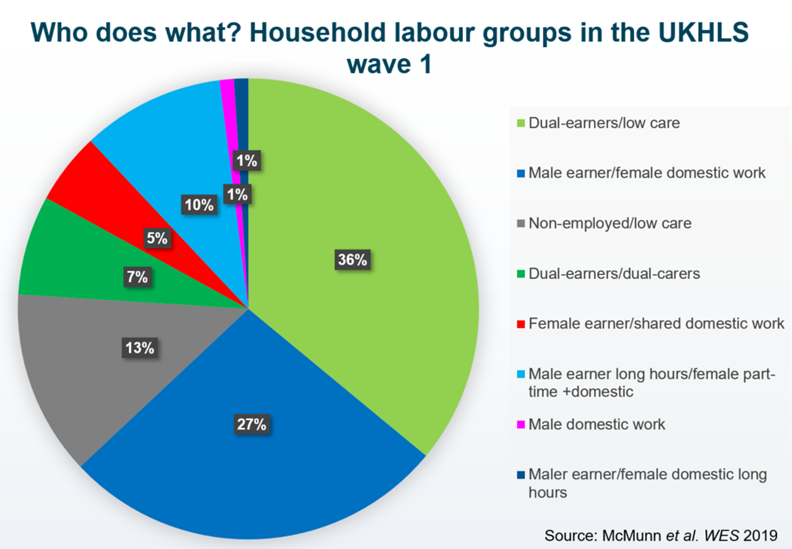

Mention of childcare is important, though, because becoming a parent continues to be a point at which gender relations are reset in households, with men still typically becoming the main ‘breadwinner’ and women more likely to move to part-time work, and to increase their unpaid work in the home.

Some of the research I’ve done with Understanding Society data has found that, to achieve gender equality in divisions of work, one person in a couple having egalitarian views is not enough in the face of slow-to-change gender norms. A shared egalitarian ideology is required. Even then, in the two largest egalitarian groups we identified (both of which involved dual-earners), women still did more domestic work than men.

It was only in female-earner couples and the very small group of men doing long hours of domestic work that men did as much or more domestic work than women. This suggests that even a shared egalitarian ideology may not be sufficient to counter potential obstacles to equal sharing in the UK.

Covid lockdowns

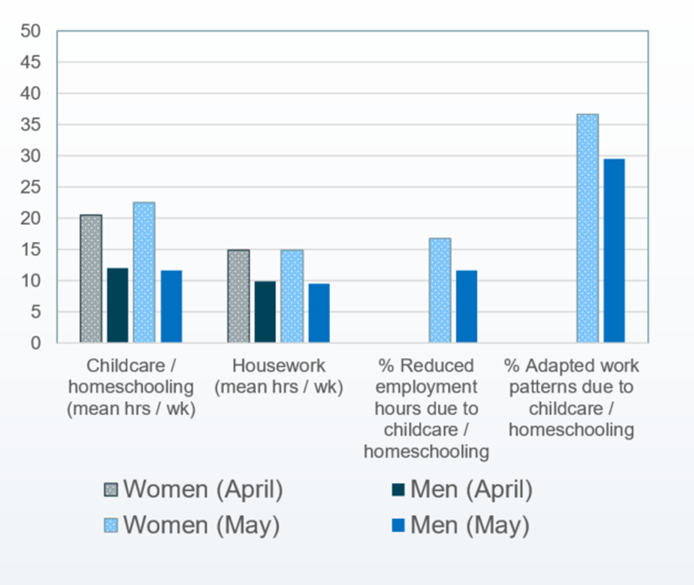

Recent events, in the form of the COVID-19 pandemic, saw these imbalances exacerbated. During the first lockdown, women spent much more time on unpaid care work than men during lockdown, and it was more likely to be the mother than the father who reduced working hours or changed employment schedules due to increased time on childcare.

We could also see the effects of this on mental health. Women who spent long hours on housework and childcare were more likely to report increased levels of psychological distress. Working parents who adapted their work patterns experienced more increased psychological distress than those who did not, and this association was much stronger if they the only one in the household who adapted their work pattern. It was also stronger for lone mothers. Fathers experienced more psychological distress if they reduced work hours, but the mother (or their female partner) didn’t, compared to couples in which neither reduced their work hours.

Health effects

This is echoed in earlier research showing that caring for other adults is linked with poor health for young women (under 45) in particular. They report more symptoms of psychological distress than women who aren’t caregivers, and higher levels of body fat – and we’ve also seen evidence that the intensity of caregiving (in terms of the number of hours per week) is linked to poorer health.

To find out more about this, I’m one of a consortium of researchers in the UK, Germany, Norway and Spain using longitudinal data to examine caregiving and its effects across the lifecourse. Eurocare is considering trends over time in:

- early adulthood (ages 16-29)

- mid-life (30-64)

- later life (65+)

- education, employment, social participation and health outcomes.

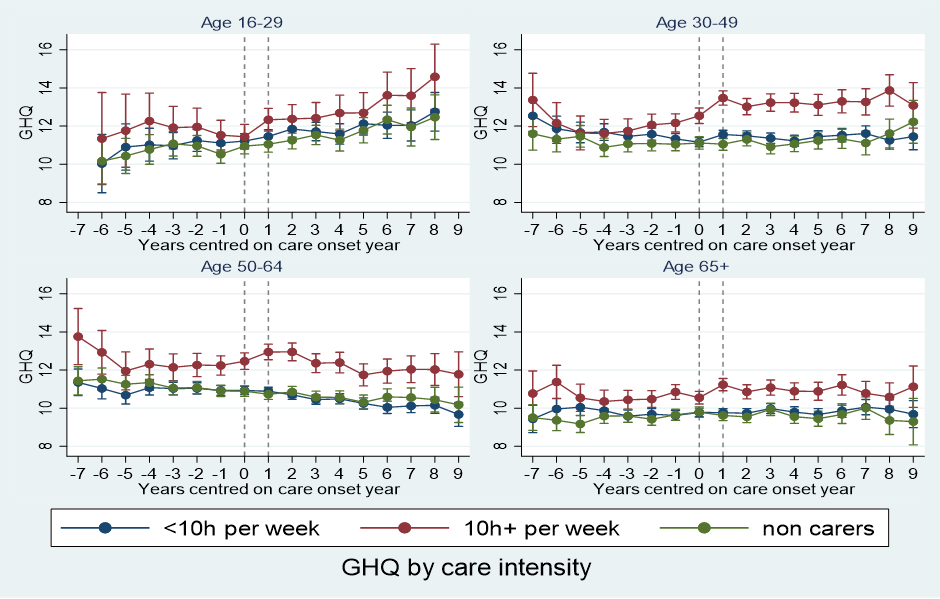

For example, we know that the health of unpaid caregivers is poorer, on average, than that of non-caregivers, but until recently there was little focus on how health changes when becoming a caregiver.

As you can see from these graphs, we found that psychological distress increased during the transition to caregiving for all ages, particularly in those younger than 64. The research also showed that it was worse for those providing care for 20 or more hours a week, and if the person they were caring for lived with them. Physical health functioning didn’t change, but we did find evidence of lower levels of functioning before caregiving.

The findings highlight the importance of identifying caregivers early, and supporting them, particularly those who become caregivers at a younger age, in order to break the cycle of becoming a caregiver and then potentially having care needs themselves in future. NHS staff, including GPs and teams discharging hospital patients, are well placed to identify caregivers.

Sandwich care

There had also previously been little focus on mental and physical health around the time of becoming a sandwich carer – someone who cares for ageing parents or older relatives while also raising children.

In a paper earlier this year, my co-authors and I found that, in every wave of Understanding Society, women are more likely to be sandwich carers than men. Among parents, the uptake of caring for a family member was associated with a deterioration in mental health, especially for those who spent more than 20 hours a week caring for a family member – and the deterioration persisted for several years. Those who cared intensively also experienced greater physical health declines during the transition to becoming a carer.

As a society, we need to recognise the unique needs and challenges of sandwich carers and provide support systems, resources, and community networks to help maintain their health – especially for those who care intensively.

Young carers, education, and work

If we turn to young adult carers (typically aged around 18-25), we can see their caring responsibilities having a detrimental effect on their education and employment prospects, too. Young adult carers are 38% less likely to obtain a university degree and enter employment than non-carers – and the number of hours they spent caring was important. Those caring for four hours a week are 47% less likely to have a degree, but those caring for 35 hours or more a week are 86% less likely to have a degree.

If we compare the UK and Germany (using Understanding Society and its equivalent, the German Socio-Economic Panel), we see that young adult carers were less likely to enter work than their peers. If they cared for more than 10 hours a week, they were 31% less likely to enter work than a non-carer. Those who had been caring for more than two years were particularly badly affected.

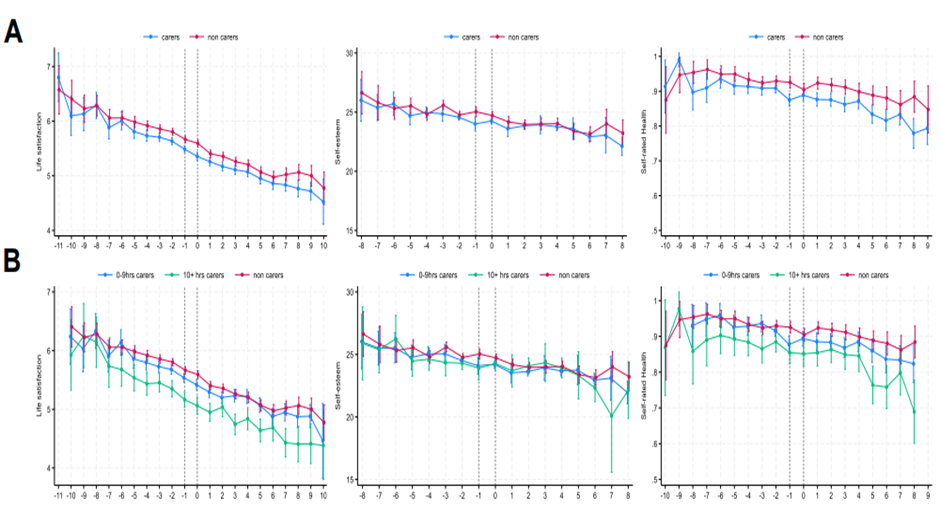

These findings underline the importance of supporting young adults who are providing informal care while going through some of the most important stages of life when it comes to building foundations for the future. This is particularly true if we look at the effects on wellbeing for young carers. In the UK, life satisfaction decreased and the probability of reporting poor health increased after becoming a young adult carer, particularly for those who reported caring for more weekly hours.

However, a systematic review of the evidence – although it showed that young carers had poorer physical and mental health, on average, than their non-caregiving peers – found very few high quality studies on this topic, so we need more research. With funding from the Nuffield Foundation, that is starting to happen.

A new paper from March this year has found that around 12% of young people became young carers, and that they had lower life satisfaction two years before becoming a carer. This difference persisted for three years afterwards, as well.

There were larger differences in life satisfaction before and during becoming a young carer for:

- young carers who cared for 10 or more hours a week /week

- those from Black ethnic groups

- those from households in the lowest fifth of income.

Again, these findings highlight the importance of early identification and support for young carers, and help for them to reduce their care load to prevent falls in wellbeing.

Health equity

The issue of caring is just one which a five-year study, running until 2029, will be looking at. Equalise: ESRC Centre for Lifecourse Health Equity will look at a range of health inequalities to generate new evidence to support changes in policy and practice. As well as issues such as learning and development inequality, we will look at ways to improve health and wellbeing for unpaid carers and working families – and to redress gender, socioeconomic and ethnic inequalities in who provides care and its impact on health and wellbeing.

I hope to publicise findings both on the project’s website and perhaps here in the coming years.

This blog was adapted from Anne McMunn’s keynote speech at Understanding Society’s 2025 Scientific Conference. It is based on several papers, which are linked to throughout the text

Authors

Anne McMunn

Anne McMunn is Professor of Social Epidemiology at University College London, and Co-Director of Equalise: ESRC Centre for Lifecourse Health Equity