It’s long been established that happiness makes a U-shape over our lifetimes – falling from a high point in youth, and then rising again after middle age. This has been mirrored in studies on unhappiness, which peaks in middle age and declines after that. However, our research with Understanding Society data shows that this pattern has changed.

Evidence from across the world has pointed to declining wellbeing for young people, but this is the first time anyone has looked at the implications of this change for the hump shape in ‘illbeing’.

Using the data

We examined Understanding Society data from 2009-10 to 2022-23 (Waves 1 to 13), particularly looking at answers to the general health questionnaire (GHQ-12), which asks about subjects’ mental health such as worry, depression, confidence and self-worth. It gives a score out of 36, with a higher score being a sign of poorer mental health. We focus on people with a score above 23, around 5% across the 2009-14 period, whom we class as being in ‘despair’.

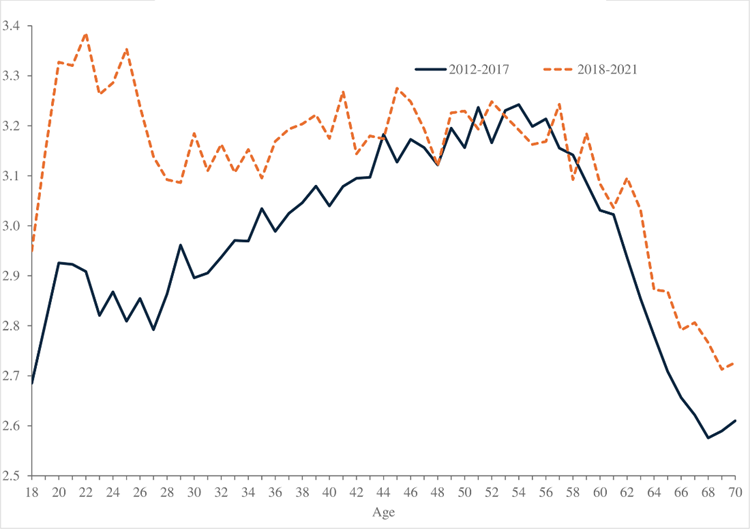

We also used data from the Annual Population Survey on anxiety from 2012 to 2021. For international comparison, we used the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) in the United States covering 1993 to 2024, which asks respondents: “for how many days during the past 30 days was your mental health not good?” Our threshold for despair (23 points) was chosen to align with the share of people in the US who reported 30 bad mental health days. Finally, we factored in information from around the world, gathered in an assessment of people’s cognitive and emotional capabilities by the Global Minds Project.

Our findings

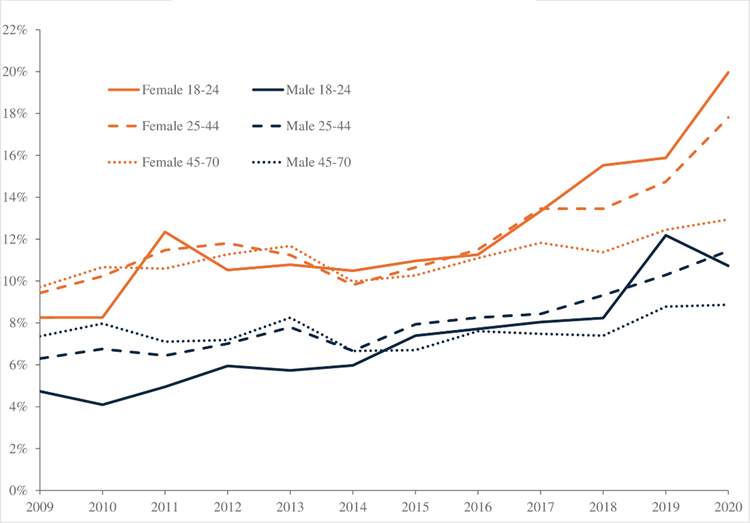

We found that, in 2009, both men and women aged 18-24 were less likely to be in despair than older age groups. But for men under 25, despair more than doubled between 2009 and 2021. The percentage of young women in despair rose even more sharply, with most of the increase coming after 2016. Levels of despair also increased for both men and women in older age groups, but the rise for the middle-aged group was smaller than for the youngest, and the rise for the oldest age group was smaller still.

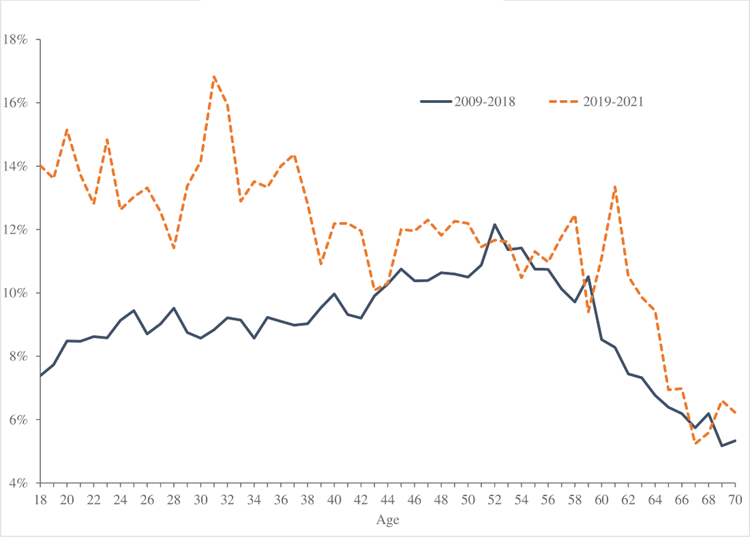

As a result, the hump shape in despair by age, which we can see here in the dark line which shows the years 2009 to 2018, has disappeared by 2019-21 (dotted orange line). Instead, despair starts high and declines with age.

We see something similar in the anxiety figures from the UK’s Annual Population Survey.

Results were similar for America. Across most of the (longer) period we studied, levels of despair in both men and women were highest among the oldest age group (45-70), and higher for the middle-aged (25-44) than the young (18-24). However, the percentage of young people in despair has risen rapidly. It’s more than doubled for young men, from 2.5% in 1993 to 6.6% in 2024, and almost trebled for young women, from 3.2% to 9.3%. Despair also rose among the middle-aged, but less rapidly. The percentage of older men and women in despair rose only a little over the period.

Finally, we found the same pattern of mental ill health declining with age in 42 other countries, using data from the Global Minds Project 2020 and 2025.

These findings are extremely significant. The U-shape of wellbeing, and hump shape of illbeing, were among the most striking, persistent patterns in social science, replicated across a number of countries and time periods. But this is no longer true. Subjective illbeing now falls with age in the US, the UK and 42 other countries – and in the US and UK we can show that it’s because young people’s mental health has deteriorated compared to that of older people.

Why is this happening?

There is research underway into the reasons for these changes, and we don’t have definitive answers yet. The Covid pandemic may have contributed to young people’s deteriorating mental health, but the growth in despair predates this. The pandemic simply exacerbated existing trends.

One obvious factor to consider is young people being heavy users of smartphones and the internet. Some research suggests that smartphone use is causing young people’s mental health to worsen – and another paper found that, when access to smartphones was limited, adults reported improved wellbeing. But, even if screen time is a contributory factor, it is unlikely to be the only or even the main reason.

There is also little evidence that the changes were driven by the 2008 financial crisis. However, it may be that the Great Recession had a ‘scarring’ effect by lowering young people’s employment prospects, and hitting wage growth ever since. The blow to public finances has also meant – in Britain and America – cuts to mental health funding, delaying access to treatment, which could make spells of poor mental health last longer.

In addition, two of us have a working paper out which suggests that paid work may be losing its power to protect young people from poor mental health. While young people in paid work tend to have better mental health than those who are unemployed or unable to work, the gap has been closing recently as despair among young workers rises.

In the end, we don’t fully understand the causes yet, but they seem to be complicated, and it’s likely that several combine together to create this phenomenon. What we do know is that this change in such a longstanding feature of our understanding of happiness through life is a major social transformation. Policymakers need to be aware of it, and to make tackling despair among young people central to any wellbeing strategy.

Authors

Xiaowei Xu

Xiaowei is a Senior Research Economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies

Alex Bryson

Alex is Alex Bryson is Professor of Quantitative Social Science at UCL’s Social Research Institute

David Blanchflower

David is Professor of Economics at Dartmouth College