We launched Understanding Society’s Insights report in February. In previous years, we have brought together research which is relevant to policy, but this time, with an election looming, we examined political interest and participation: what drives voters’ behaviour? How do our lives affect our vote?

Speakers from universities across the UK and Europe introduced research which addressed two specific themes:

- young people – what influences political interest and participation during this critical life stage?

- changing lives and communities – how do factors such as home ownership, the communities we belong and the life events we experience influence our voting behaviour?

Our keynote speaker was Ben Ansell from the University of Oxford, who opened the day by talking about ‘Britain Divided’, providing the first two key messages:

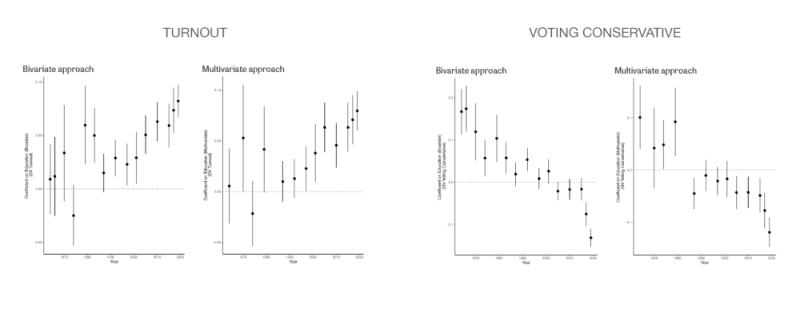

Ben used data going back five decades or more to show that education level is increasingly a predictor of turning out to vote. This was true whether taking a bivariate approach (looking solely at age and turnout) or multivariate (taking other factors into account such as income or gender to reduce bias).

Our education divide

In addition, while in the 1970s and 1980s it was still the case that people with degrees were more likely to vote Conservative, over the decades that trend has completely reversed. People with higher educational qualifications are now significantly more likely to vote Labour.

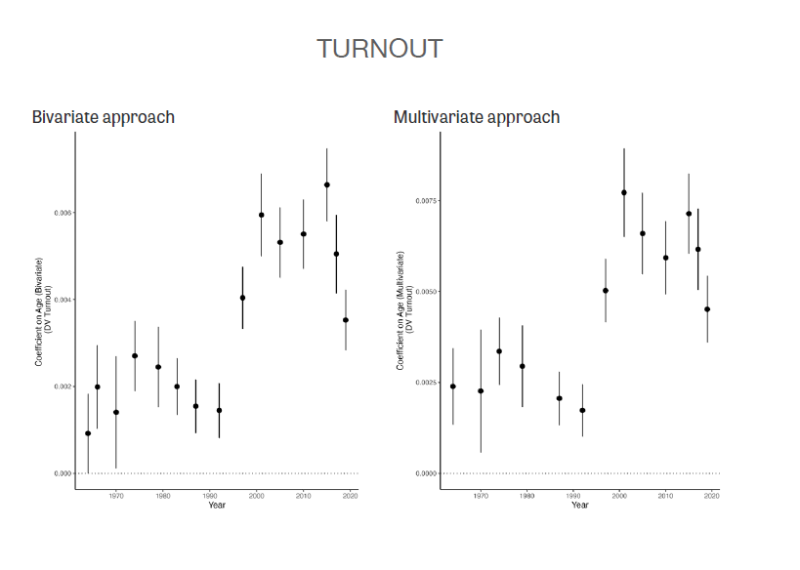

We know that older people are more likely to vote than younger people, but this has become particularly true in recent decades. This widening age gap is of particular concern in an ageing society that is making a larger call on society’s resources.

Our age divide

This finding leads naturally on to another, mentioned in the chapter on young people in our Insights report:

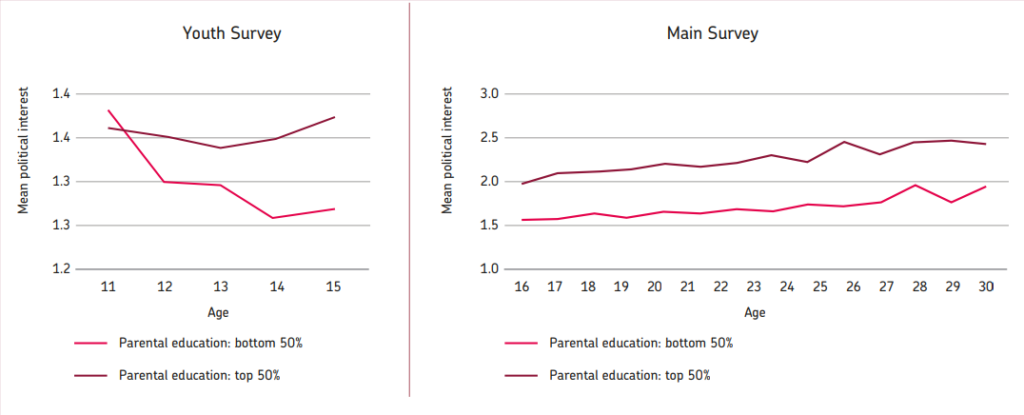

Jan Germen Janmaat and Bryony Hoskins used the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and Understanding Society to look at people’s family background and their engagement with politics in adolescence and early adulthood.

Using answers from our Youth Survey of 10-15-year-olds about how interested they are in politics, they found that, between the ages of 11 and 15, young people with educated parents were becoming politically engaged more quickly than those with less educated parents, but from mid-adolescence to the age of 30, this aspect of their social background remained the same.

In other words, at the beginning of adolescence, there are no social differences in political engagement, but these differences soon appear, and grow wider at ages 14 and 15. After 16, they stabilise, but with young people from educated families showing consistently higher engagement levels than those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Put simply: better-off people and older people are more likely to vote. In the words of Jan Germen and Bryony’s work with Nicola Pensiero for the Nuffield Foundation, this is “problematic for democracy as it skews democratic decision-making in favour of the privileged and undermines the public legitimacy of democracy”.

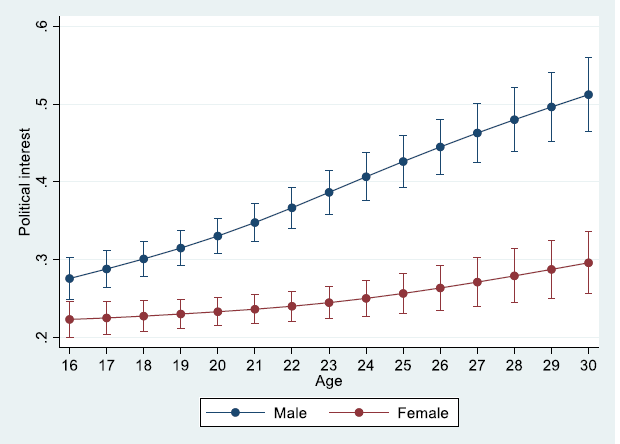

Jan Germen’s presentation at the event also highlighted a gender gap on political interest which opens up between boys and girls, and increases during adulthood, with young women less interested in politics. The gap is particularly noticeable among young women who pursue a vocational pathway in education, but there is no similar gap among young men.

There was some discussion at the Insights event as to why this might be, with some speculation that our adversarial style of politics might be off-putting for girls and young women, or that they find it more difficult to see the relevance of political decisions in their day-to-day lives.

Georgios Chrysanthou presented findings from research he’d done with María Guilló which examined five electoral cycles between 1992 and 2014 using BHPS and Understanding Society. They wanted to test the economic voting hypothesis: the idea that voters change their political preferences based on their personal economic wellbeing.

This research showed that the economic voting hypothesis was true in elections held close to economic downturns – but subjective financial evaluations were insignificant in periods of relative economic stability and growth. Ultimately, they concluded that voters’ economic perceptions are better drivers of economic voting than actual objective income measurements such as household or individual annual earnings.

6. Class factors appear to be waning

Class factors in politics seem to be becoming less important for some types of political outcome. Income, home ownership and local wealth are still important for voter turnout, but less so for voting Conservative.

For example, we know that people on lower incomes, and with other socio-economic problems, show less political engagement than those who are better off. Sebastian Jungkunz and Paul Marx used Understanding Society to look at whether changes in income had any effect on this. In other words, if someone is born poor, and therefore statistically less likely to vote in later life, but becomes better off, does that make them more likely to vote?

Comparing our figures with other panel datasets from Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland and the US showed that, in fact, even if we get richer, we don’t get more engaged with politics than we otherwise would have been. It seems that our position in society when we are born affects us more than we may think.

It’s long been assumed that homeownership makes people more likely to vote for conservative (and for incumbent) parties. Research has shown that council house tenants given the right to buy their property, for example, were more likely to be conservative than non-buyers. However, these findings tend to be based on cross-sectional studies. Sinisa Hadziabdic and Sebastian Kohl used Understanding Society, the German Socio-Economic Panel and the Swiss Household Panel, to compare three European countries, and found that people are more likely to be interested in politics and to have a partisan preference if they own property, but homeownership doesn’t make people more conservative. In the UK, it brought them closer to (New) Labour – and the change isn’t sudden: homeownership is part of a long-term shift in people’s political views.

One of the reasons why inequalities in young people’s vote matters is that voting is a habit – people who don’t vote at their first election are likely to remain lifelong non-voters. However, Lauri Rapeli, Achillefs Papageorgiou, and Mikko Mattila used 27 waves of data from BHPS and Understanding Society to show that when people move in together, divorce, lose their job, and/or retire, the life disruption often alters their habits.

Moving in with a partner makes people more likely to vote, for example, while divorce and widowhood make voting less likely. Retirement increases turnout, but only for habitual voters. It may be that habitual voters find that retirement means more leisure time and mental capacity to engage in politics, and habitual non-voters withdraw more from social connections that might otherwise encourage them to vote.

Magda Borkowska and Renee Reichl Luthra examined whether the experiences which shape young people’s political engagement are different in immigrant families. They found that parental education is less important for these families than it is for those with two UK-born parents, but that becoming a UK citizen (or being a Commonwealth citizen) is significant, because it brings with it the right to vote. Children with at least one naturalised or UK-born parent are more likely to be politically interested, and, through seeing their parents voting, more likely to vote themselves.

Decreasing barriers to citizenship, then, and promoting voter registration among immigrants can greatly enhance the political integration of immigrants and their descendants.

Tak Wing Chan and Juta Kawalerowicz examined David Goodhart’s idea that the UK is divided into “people who see the world from Anywhere and the people who see it from Somewhere”. They found that, in fact, ‘anywheres’ are just as attached to their communities as ‘somewheres’, if not more so. “Somewheres”, they wrote, “are better described as nationalists than as communitarians.”

However, Franco Bonomi Bezzo and Anne-Marie Jeannet showed that “neighbourhood deprivation is associated with lower norms of civic obligation”. Membership of organisations such as parent associations, tenant groups, social clubs, and voluntary service groups in deprived areas is lower than in more advantaged areas. However, membership of political organisations is more likely in deprived neighbourhoods. It may be that in deprived areas, people have fewer alternative routes to influencing politics or spend more energy on community work which aims to bring about social change, and less on hobbies, leisure, or socialising.

Going back to Ben Ansell’s keynote speech, he found “no evidence that it is demographic differences, associated with a ‘new elite’ that are tearing Britain apart … our political system is more than capable of doing that” on its own.

Instead, he argued, based on UK population surveys he ran with YouGov in 2012 and 2022, “what divides us is our partisan attachments … Parties are about converting our differences of opinion into differences of policy.”

Daryna Grechyna used BHPS and the European Social Survey, and found that polarisation fell between 1991 and 2007 – but rose again significantly, especially after 2010.

She said the fall in polarisation might be explained by ‘New’ Labour’s move towards centrist social democracy in the 1990s, while the increase may be linked to the growth in immigration after 2004, the 2008 financial crisis and ‘great recession’, and the Brexit Referendum. One thing was clear, though: political polarisation in the UK is lower when the employment rate is higher, or when the number of UK-born residents in a county is higher. Polarisation is higher when there is greater variation in people’s employment status – that is, there is a greater mix of people in the county who are, for example, employed, self-employed, unemployed, retired, or off sick.

The report

This research reveals some of the fundamental drivers of political participation, revealing how deeper factors in people’s lives and society are intertwined with political participation. These findings tell us more about the long-term health of British democracy, and point to key areas for action or reform that political parties should take on board as they pull together their manifestos for the general election.

There are many more examples of what the data can tell us about political identity and electoral behaviour in Insights 2024

If you’re interested in the research presented you can find the presentations below

Jan Germen Janmaat – Social and gender gaps in youth political engagement

Sebastian Jungkunz – Economic conditions and political socialization

Stuart Fox – Can youth volunteering reduce inequalities in turnout?

Georgios Chrysanthou – Economic determinants of individual voting behaviour in UK general elections

Lauri Rapeli – When life happens: the impact of life events on turnout

Renee Luthra – Socialisation disrupted

Franco Bonomi Bezzo – Civic Involvement in Deprived Communities

Tak Wing Chan – Anywheres, Somewheres, Local Attachment, and Civic Participation

Sinisa Hadziabdic – Is the Left Right?

Authors

Chris Coates

Chris is Research Impact and Project Manager at Understanding Society

Raj Patel

Raj Patel is Associate Director, Policy and Partnerships, at Understanding Society